Cairo, Egypt (photo by Jason Wilson).

After two and a half weeks in Egypt, we thought about pivoting, leaving for good. We had just picked up our passports after extending our visas at the Mogamma complex off of Tahrir Square in Cairo.

Extending our visas was easy, if complicated. The building was filled shoulder to shoulder with people applying for everything from refugee status to residencies. A crowd of languages and personal anxieties down every labyrinthine turn. Cats ran through the hallways; stacks of paperwork reached the ceilings. There wasn’t a computer in sight. Passports were handed back out of a cardboard box, the woman behind the counter holding each one up, and its owner squirming through the push of bodies to retrieve it. It was like something out of Kafka.

The process took a day longer than expected, which is why my husband, Jason, and I were still in Cairo when we woke up to the news about the bus. The day before, February 16, 2014, a member of Ansar beit el-Maqdis (the top Islamist group in Sinai, now part of ISIS) had hurled a bomb on a bus of Korean tourists about to cross the border to Israel. Three people were dead.

For the first time in our travels through Egypt, the first time in our thus-far eight months of travel through North America, Europe, and the Middle East, we were worried. Sitting on our double bed in our small hotel room amidst peeling paint, we took out our laptop and opened up a new Word doc. We started making lists:

- We could A. Get on our overnight bus to Dahab, a small town on the Red Sea coast of the Sinai Peninsula that night as planned. From there, we could give it time. If needed, we could get a bus to Sharm El-Sheikh, where we could hop an international flight anywhere. Or we could head in a different direction, to Nuweiba, where we could get a ferry to Jordan.

- We could B. Stay put. It would be no problem to extend our stay at our hotel; there were hardly any guests. We could wait it out, catch the pulse of Cairo, see if anything more happened.

- Or we could C. Bounce now. We could book a flight to Jordan or Germany where we had friends, or on to Thailand, where we wanted to travel next in our 16 months of around-the-world travel. Protests were erupting in Bangkok, however, and we realized that we could escape the frying pan and head straight into the fire.

We also made lists of what levels of threat would be acceptable. Any more tourist bombings and we’d leave. No matter what.

It was a strange list to make. To think about. To try to look out into the days ahead of us and predict peace or violence. To think that there might be someone out there in Cairo right now who would be dead at the hands of extremists that day, or the next, or the next, and to decide what we would do to save ourselves.

Jason worried that if we went to Dahab, we’d like it too much and decide to stay despite anything that happened, despite a heightened level of threat.

But we chose option A and got on the bus.

***

Up until the bus bombing, Egypt had been wonderful, albeit challenging. It was a place where people exuded warmth, inviting us for tea as we walked through neighborhoods or helping us when we were lost. Hotel owners and guides talked to us for hours about the political climate.

View overlooking Hatshepsut’s temple (photo by Jason Wilson).

The tourist attractions were virtually devoid of other tourists. We stood alone with our guides at some of the lesser-known pyramids, soaking in the monumental ancient wonders, a few lone humans in a blip of history.

But it was also a place of confusion, of people badgering us to buy their plaster sphinx statuettes, take their tour, eat at their restaurants. At the Great Pyramids, we could hardly see the sites for the number of people trying to sell us tchotchkes. One man took a scarf out of its wrapping and tried to put it on Jason’s head. The man insisted that it was a gift, but we knew how it would go. He’d ask for a monetary gift in return. He followed us, shouting, shouting as we walked away.

Strolling down the street in Aswan, we were hounded by captains selling boat tours. In Luxor, it was carriage rides.

We were overcharged or lied to almost daily. One time, after my anger melted away over someone trying to raise the price we’d agreed upon, I started laughing hysterically from the chaos of it all.

I felt uneasy about getting mad. People were trying to go about their lives, to make ends meet in a next-to-impossible situation, and if I got ripped off a dollar or ten or even twenty here or there, wasn’t that just part of the cost of being there, guests in someone else’s country?

It was a question of cultural differences. In my Midwestern American culture, lying is a sin. Religious or not, it’s a sin. A taboo. An offense. A no-no. It is war, not a skirmish.

And yet.

And yet I fell in love a little bit.

In the end, there was a lot more love, more smiles, more joy than any anger could wash away.

One of the lesser pyramids (photo by Jason Wilson).

Numerous times Egyptians (especially young people) asked to take a photo with us, just for the novelty of it. Some asked us to put our hands into a “C” shape for Sisi , which we declined. General Sisi came to power with the support of the military after deposing Islamic-Brotherhood President Morsi, who was democratically elected after Egyptians overthrew the dictator Mubarak during the Arab Spring two years before. The Egyptians we met loved Sisi, at least outwardly. And they seemed to love us, too.

This was not the Egypt of the Western press. Sitting in our hotel room, I read an article from a Minnesotan paper, describing the “kill-or-be-killed streets of Cairo.” Kill or be killed? Danger? From the traffic, maybe.

“Stay out of Cairo on Fridays” was our mantra, our way to avoid the weekly protests and occasional bombings that came with it. This was the only precaution we felt like we needed to take.

Egyptians asked us to please, please go home and tell people that Egypt is safe for tourists.

***

The overnight bus to Dahab was unpleasant, more than most overnight buses. Beyond sleeping upright over bumpy desert roads, there were several checkpoints along the way, at which guards would board to check our passports. It happened so often that between checkpoints Jason nodded off into something that only resembled sleep with our passports in his hand. In a sleepy haze, we disembarked at one stop, and stood in a line, while guards unloaded our luggage and brought dogs through to sniff our bags.

While annoying in our sleepy state, this was forgivable, even reassuring. The Sinai Peninsula is a mountainous desert, and while we went south and then across, rather than through the north, where Ansar beit el-Maqdis loomed large, I could imagine the bus coming under attack on the dark roads.

***

Dahab by day (photo by Jason Wilson).

We didn’t pick Dahab out of a guidebook, or off of a travel website. Dahab is a small town, popular with backpackers, the cheaper, low-key, hippie answer to the resort city of Sharm el-Sheikh. We first heard about Dahab at a hostel in the Israeli desert, and then again at one in Wadi Musa, the town outside of the ancient city of Petra in Jordan. Go to Dahab, people said. They told us that you could get a dorm bed at a hostel with a pool for $6 a night. Two people could get an apartment for about the same cost as two dorm beds.

Backpacking through the Middle East is much different than other regions. There are few party spots and it’s generally not as cheap as places such as South East Asia. It’s also more difficult and less romantic than traveling through Europe. This weeds out a lot of the worst backpackers—those who seek cheap beer and full moon parties about all else, or those whose travels are funded by their parents and so agree to stick to the supposedly safer Western countries.

The only place resembling the backpacker hotspots of the world in the Middle East is Dahab. Some of the world’s best diving is right off of its shores. It is also one of the cheapest places to learn to dive. It’s still the Middle East, which means that while shisha pipes and tea are cheap, alcohol is not, and while bikinis are O.K. on the beach, they aren’t elsewhere in town.

Dahab is like the center of a swirling eddy, the spot all backpackers in the Middle East are angling towards.

The Middle East is cold in the winter. Buildings are made of cinderblock, doing little to insulate those inside. When we woke up in Bethlehem on Christmas morning, we could see our breath in our bedroom. But Dahab is far enough south that the waters are warm enough to swim in year-round.

The whole region is a constant shuffle of deep spirituality and modern growth, welcoming strangers and stubborn shopkeepers. I would live in Istanbul, Tel Aviv, or Amman in a heartbeat.

But we were getting tired. Long-term travel is not easy; it’s not like being on vacation. It takes budgeting and determination. Every few weeks we had to learn the fragments of a new language, conversions of a new currency, new systems of transportation. Dahab became our beacon of hope, a spot to rest at the end of the long dusty road. We planned to rent an apartment and stay for a month.

***

We arrived in Dahab and began looking for an apartment. But by that afternoon some asshole tweeted from an account allegedly associated with Ansar beit el-Maqdis that all tourists had 48 hours to leave Egypt before they would start targeting tourists. The first bus bombing had just been a warning.

This flew in the face of our lists. The level of threat escalated, and we had said that we’d leave if that happened. We should have been getting on a ferry to Jordan.

But we stayed. We asked around. What did the Egyptians and expats who lived in Dahab think?

The Egyptian motto was “When it’s your time, it’s your time.” It was a kind of inshallah—an Arabic word that means God-willing, and permeates Arab mentality—in the face of terrorism.

The expat position was “not here,” and more annoyance or anger than fear. Dahab is small and was only at 20% capacity, tops. It didn’t seem like it would be worth anyone’s time and effort to set off a bomb there. But it had been bombed before, back in 2006, and many Egyptians and expats remembered it.

There were rumors of European airlines cancelling flights, of foreign governments increasing levels of travel advisories. This was the direction of the expats’ anger. Chris, a British expat who owned a hotel in Dahab looked at it this way. “Could you imagine,” he said, “during the 70s when the U.K. was ostensibly in a civil war (with the IRA), international airlines cancelling trips to London?”

We read news stories about the bombing, about the tweet, articles dashed out against deadlines by people who weren’t in the country. After reading the Minnesotan newspaper article earlier, we didn’t trust the Western media to convey nuance or reason. But the fear those articles carried wheedled their way into our brains nonetheless.

Jason called the U.S. embassy in Cairo. Their advisory hadn’t changed from before we came to Egypt: don’t go if you don’t have to.

Their sanguinity came as an unpleasant surprise. The only advice they were willing to give us was to follow them on Twitter and register with them online, giving them our address in Egypt. I guess this was so we could receive alerts if something happened.

I memorized what time the bus left for Nuweiba and the ferry left for Jordan.

We sent emails to a friend in the U.S. military, and a friend of my parents’ who works for the State Department, asking for advice.

But we continued to hunt for an apartment. We picked out which dive shop we’d book lessons with.

And we followed @USEmbassyCairo on Twitter.

***

I learned more about the political situation in Egypt than I did in any other country. More than Israel or Palestine or Thailand or Burma or Norway. Everyone talked about it, and everyone was eager to share. And we were eager to listen.

Sitting in the small lobby of his hotel in Cairo, Mohammed, a hotel-owner, chain-smoked, filling the air with each exhale. He’d quickly put his cigarette out when we walked in, and open the doors to the balcony, six stories above the noise and congestion of Cairo traffic.

He’d settle back into his old leather chair, and we’d sit around, talking about what was going on. People seemed happy. They seemed to like Sisi, which we, born and raised in the religion of freedom, couldn’t quite wrap our heads around.

“It’s like you are leaving here, and driving to the airport,” Mohammed said. “And the traffic stops—you’re in a traffic jam—but at least you are facing the airport. You are facing the right direction.”

With Morsi, he explained, it had been as if the car was facing the wrong way, without hope of ever getting where they wanted to go.

I looked out towards the balcony, and thought about the aptness of that simile in a city where it could easily take 45 minutes to go three miles in a car.

***

When people ask me if I was scared in Egypt, I say no. This is a half truth, rounded up to a whole in the polite conversation of backyard barbecues, told over cocktails when the balance of conversation requests that I inquire about the other person’s job or new house in a moment.

The truth is more complicated. We were scared before we went to Egypt. Each time Egypt appeared in the news, I’d message my friend Ahmed, an Egyptian who lives in Cairo, whom I’d met through Couchsurfing.org when he visited Seattle for a conference.

“Are you sure it’s still safe?” I’d write. And he’d give me the same response.

“Yes, it is safe. It is more like your Occupy protests.” There are no bombings associated with our Occupy protests, I’d think to myself.

Our fear dissolved when we arrived in Egypt. For the first two and half weeks in Egypt, we were never scared. As we travelled up and down the Nile, we had no fear. We did indeed stay out of Cairo on Fridays, and I felt at ease walking down the street by myself.

But after the bus bombing, that changed. Of course we were scared.

In Dahab the fear bit at us like sandflies, invading our tranquil paradise. Indecision kept us in an overworked state. Our brains kept cycling, analyzing, configuring, questioning.

Jason said that he felt like my safety made him more nervous than his own—the imagined guilt he’d face if something happened to me while he lived. Usually I’m the macabre one.

Our mothers fretted over us via email. Was this fair to do to them? And could we get the rest that we needed if we felt this way during our entire stay?

We were heartbroken. We were upset for the Egyptian people whose lives this was ruining. Not only tourists were fleeing Egypt, so were foreign businesses and investors. Farther outside of Dahab we saw the skeletons of resorts that had been constructed in the twilight of Mubarak, beam structures rusting in the desert sea spray.

Here we were, with the gold ticket that is an American passport, and we could just leave. If things got really bad, so could the expats, though they might have to leave businesses that it took them years to build and saddle their Egyptian partners with the shells of their hotels and dive shops.

***

Two days after the terrorist of Twitter made his threat, we packed to leave. The fear was clawing at us, bogging us down. We felt terrible. We felt powerless. Children in a dark forest. As we packed, an email from our friend in the military came in.

My parents’ friend at the State Department had already emailed to say that he thought that Dahab sounded like a nice place, and we’d probably be O.K, but we still packed.

Our friend’s email said that he’d done some asking on our behalf, and thought the same. We were fine down in Dahab.

This tipped the scales. It was a tremendous relief. Nonbiased people, who still cared about our personal safety, told us, in their expert opinions, to stay. It was advice no newspaper or government had been willing to give us.

This was an important moment in my life. It was the day I took my agency back.

There wasn’t much two ordinary people could do in the face of terrorism. But we could stay. We could shop at the local fruit market and choose a dive shop that employed Egyptian instructors.

We could send a message, with our wallets, that we wouldn’t give in to threats. We could say fuck you to terrorism.

***

Sunrise over Dahab (photo by Jason Wilson).

Not everyone stayed. A German couple who were staying at the same place as we were changed their vacation plans and went to Jordan instead.

As the weeks went on, we saw fewer and fewer new faces. Eventually, the Dutch and German governments recalled all tourists. There was much speculation around town that this was a CYA scenario, more for insurance purposes than actual threat.

The day we should have left, the day the warning was up, when tourists were supposed to become a target, nothing happened. We found our perfect apartment that afternoon, paid a month in full that night, and moved in the next day—my 31st birthday.

We let go of our fear and fell into a routine, doing yoga most days, diving or snorkeling in the mornings, cooking healthy meals, making friends. We listened to a lot of Jack Johnson. I started writing a novel.

***

More than a year later, I woke up, back in my Seattle bed, to an NPR news story. My brain was still sticky with sleep, and I wanted to believe I was dreaming. A Russian plane blew up leaving Sharm El Sheikh.

“That’s it,” Jason and I said to each other. “It’s done.”

Who would go now? Who would book their vacation to a warm-weather paradise when 200 tourists had just died there? Why go when you could go to Bali, to Mexico? Why go see the Pyramids when you could go to Petra, to Machu Pichu?

All of those empty shops. All of those desperate people, trying to live their lives, trying to get by. No customers in sight.

Every morning for the next week, I woke up to a story about the investigation, slowly unwrapping day by day, in my sleepy, king-sized bed. Safe and warm and on the other side of the world.

“There’s a saying,” one person said during one morning’s coverage. “In Egypt, tourism gets sick, but it never dies.”

I hoped so.

The daily news coverage only changed when, two weeks later, terrorists overran the Bataclan in Paris. I watched the recovery, listened as the weeks unfolded to people explaining that going to Paris was perfectly safe now, that the surrounding cafes had reopened for business.

Terrorism is a hell of a thing. It’s a hell of a thing because it works so well. Because fear is powerful. Because we are so perceptibly mortal.

***

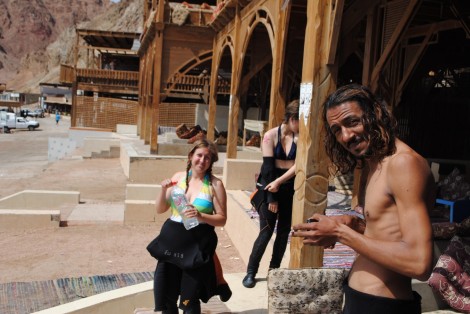

Me and Mohsen (photo by Jason Wilson).

Steps from Dahab’s shore is some of the world’s best diving: clear water as far as the eye can see brimming with sea life. And just outside of town, at the Blue Hole, it’s even better.

Beneath the surface, 30 meters below sea level, there are no politics. Just fish, bright flashes of yellow and blue and orange, their fins lit from the sunlight filtering down through the depths.

Underwater, I trusted my life with my Egyptian instructors, Mohsen, Walid, and NuNu. And they trusted theirs with me. They trusted me to control me breathing, to communicate through hand signals, and above all else, to relax.

Judy T. Oldfield’s work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Stranger, The Portland Review, and Saveur (online), among others. She holds a B.A. in English and Comparative Religion from Western Michigan University. When not traveling, she lives in Seattle with her husband, Jason.

Great read. I’m based in Israel and I understand the feeling of fear you experienced. Unfortunately terrorism is something that you get used to, but the “life should continue regardless” attitude you described is pretty much the finger to the face answer to terror.

Sounds like you had a great journey, I’ve started a journey of my own, 1000 trips to Everest. would love if you get a chance to read about it.

keep living the life;)

LikeLike