Dilruba Ahmed is the author of Bring Now the Angels (Pitt Poetry Series, University of Pittsburgh Press, April 2020). Her debut book of poetry, Dhaka Dust (Graywolf Press), won the Bakeless Prize. Her poems have appeared in Kenyon Review, New England Review, Ploughshares, Poetry, and The New York Times Magazine. Her poems have also been anthologized in The Best American Poetry 2019 (Scribner), Halal If You Hear Me (Haymarket Books), Literature: The Human Experience (Bedford/St. Martin’s), Indivisible: An Anthology of Contemporary South Asian American Poetry (University of Arkansas), and elsewhere. Ahmed is the recipient of The Florida Review’s Editors’ Award, a Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Memorial Prize, and the Katharine Bakeless Nason Fellowship in Poetry awarded by the Bread Loaf Writers Conference. She holds degrees from the University of Pittsburgh and Warren Wilson College’s MFA Program for Writers.

Curtis Smith: Congratulations on Bring Now The Angels. I really enjoyed it. Being part of the Pitt Poetry Series is quite an achievement. Can you share the manuscript’s path and how it found a home with Pitt?

Dilruba Ahmed: Thanks, Curt! I received the good news from Ed Ochester in March of 2019. The acceptance note came from an unfamiliar e-mail address, so initially I was uncertain!

Over the course of 2-3 years, I’d sent versions of the manuscript to various presses, revising heavily (and retitling) several times. In fact, Pitt rejected an earlier version of of the manuscript in 2018. Various precursors to Bring Now The Angels were a two-time finalist for the Kundiman Poetry Prize from Tupelo Press; a semi-finalist for the Lena-Miles Wever Todd Prize from Pleiades Press; and a 2nd runner up for the Benjamin Saltman Award from Ren Hen Press.

Even after Pitt accepted the manuscript, I subjected it to another round of substantial updates before submitting the truly finalized version to the press.

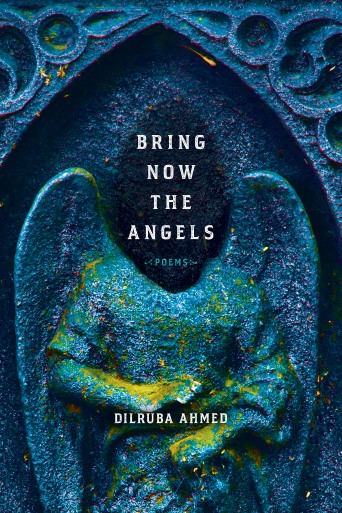

The staff at Pitt are lovely people and I can’t thank them enough for their support of my work, and for the amazing cover they created. All along the way, I was lucky to get the feedback of several trusted readers to guide my revision process, especially that of my dear friend, poet & editor Ross White, whose book Charm Offensive is forthcoming from Eyewear Publishing. He & I have been trading poems and draft manuscripts for years. My poems evolved only with the gift of Ross’ keen eyes on them.

CS: The collection starts with a beautiful poem on forgiveness, but as I continued reading, I felt that poem’s shadow stretching over much of the collection. Was this your intention? I felt as if the forgiveness you addressed was the kind that was a gift not just to others but to yourself.

DA: Thanks, Curt! I wrote a little about this poem for The Best American Poetry 2019, for which “Phase One” was selected. You’re right: when the poem emerged I had been thinking a lot about the notion of self-forgiveness as a precursor to broader forgiveness. At the time, I was struggling with strong feelings about the political situation in our country. While I found an outlet for some of those feelings via local activist groups, I was still carrying a lot of anger and resentment.

I was fumbling for a way forward in a country so bitterly divided across political lines. The idea of turning inward, first, as some kind of initial step, felt both genuine and viable to me. The notion that the understanding or forgiveness that we might hope to extend to others must begin within began to resonate with me.

For me, the question remains about whether healing and forgiveness are possible—or even warranted—in some scenarios. (This question feels even more fraught now, in the midst of pandemic crisis, during which countless lives face harm by our country’s misguided “leadership.”) In the meantime, this poem happened. While it is very much a self-address, I hoped it would resonate beyond the self.

CS: The poems in the book’s first section focus on your father’s illness and death. I’ve been through a similar situation, and I found the experience to have a strange duality because I was experiencing it both as a son, with all its first-hand intensity, and also as a writer, who was desperate to understand it all in a different way. May I ask if you also experienced things this way—almost as if you were watching it all through two different lenses? I also found writing about the experience to be difficult but also very helpful to the healing process. Did you experience this? Did you need some distance between these events and the time you sat down to write about them? If so, what do you think you needed to get right in your thoughts before putting pen to paper?

DA: I’m very sorry to hear that you experienced something similar, Curt.

It’s possible that being a writer means that everything involves a bit of an out-of-body experience. I’ve definitely felt at times that I’m floating above or outside my experience even while it’s unfolding, trying to gain some perspective on it, and make meaning of it. It’s sometimes hard to turn that mode off.

I tried to write during the time of my father’s illness. But nothing felt authentic to me, largely because I was avoiding so many of the concerns that suddenly eclipsed everyday life.

About a year out from my father’s death, something inside me dissolved, and in what felt like a relatively short time, I wrote many of the poems that formed the book.

The writing was immensely painful but also essential to my healing process. I’d been unable to genuinely engage with my writing until the passage of time prepared me for facing the difficulties directly.

Even then, I wrestled with forms that could house the content, both because the experiences felt “unsayable” as Marie Howe describes, and because grief’s weight felt relentless. And even still, the process is ongoing: the grief, the writing, the healing.

CS: I discovered a different vibe in the book’s second half. There are many references to children and snapshots of the America we live in now. Did you see the mood of this second half as a kind of a counter—or perhaps a complement—to the first half?

CS: I discovered a different vibe in the book’s second half. There are many references to children and snapshots of the America we live in now. Did you see the mood of this second half as a kind of a counter—or perhaps a complement—to the first half?

DA: While the first half deals with personal loss, the second half of the book broadens to other forms of loss. Loss of the earth as we know it. Dreams we may have had for our lives and our children’s lives. Faith in structures and processes meant to serve our country. Loss of human dignity. Through it all, the poems still search for a sense of faith and hope.

CS: When I’m writing nonfiction, I find myself reading poetry. I’m not a poet, but there’s something about the language and the rhythms that fits my nonfiction sensibilities. I lack the proper words to describe this link between poetry and nonfiction, but I felt it in a different way when I read the first half of your book. I thought those poems read like a linked narrative, a story told in a novel and very touching way. As you ordered the pieces in the first section, did you lay them out in a way that told a larger story about you and your father? Do you see any links between the language of poetry and the nonfiction writer’s desire to share a story?

DA: Yes, absolutely. Your description of the first half as a linked narrative is spot on.

The gesture to give shape to experience via language is so fascinating to me, and part of what we share across genres.

Maybe that’s what you’re noticing: our need as writers to bring shape, structure, and meaning to lived experience through language, in ways that feel authentic and emotionally true. The interplay between showing and telling, between a narrative impulse and a lyrical one, between revelation and restraint, between language in concert with content and language cutting against content—across genres, these elements are sources of tension and energy.

CS: I admired the tone of these pieces. There’s such emotion, yet there is also a kind of calm, a kind of clear-thinking compassion. I think that must be a hard road to navigate. I know it varies from poem to poem, but overall, how would you describe your tone? Does voice come naturally or do you find yourself wrestling with it? Or does it depend on the individual piece?

DA: I think it depends on the individual piece. I tend to resist the idea of “voice.” That’s probably because I’ve come to regard my role as serving the needs of the poem.

While I may initially give voice to a particular experience, feeling, or thought, in revision stages, I try to listen hard to what the poem is telling me. The more expansively I can imagine the poem’s possibilities, and the more equipped I am with an array of craft strategies, the better prepared I am to serve the poem’s needs. It’s a continual process of listening and learning. Sometimes, it’s difficult to listen well!

CS: Can we talk a bit about process? What usually comes first for you—an image, a line, an idea? There are many different forms in the collection—when does structure come into play? Do you have to know the form before you start—or do some pieces dictate their shape to you? Do you work in creative spurts or are you an everyday, no-matter-what writer?

DA: Yes to all three: poems have come to me as an image, a line, and an idea! Most often, however, poems come as a snippet or a line.

For example, a couplet has been rolling around in my head for a couple of weeks now. So I’ve been trying to figure out whether it wants to be a ghazal, or maybe a sonnet. Maybe it’s the start of a free verse poem with deep enjambment that obscures its rhymes. Or maybe the rhyme is actually holding it back. Earlier in my writing, I had less patience about this kind of incubation phase and was more likely to try to wrangle the poem into existence.

Sometimes I’ll set out to write a certain type of poem – a villanelle, or a ghazal—but often structure comes into play in the revision phase.

CS: What’s next?

DA: Some new drafts are emerging! And I’m super excited to be offering online writing workshops through a new venture called THE WRITING LAB.

Curtis Smith has published more than 100 stories and essays, and his work has appeared in or been cited by The Best American Short Stories, The Best American Mystery Stories, The Best American Spiritual Writing, The Best Short Fictions, and Norton Anthology New Microfictions. He’s worked with independent publishers to put out two chapbooks of flash fiction, three story collections, two essay collections, four novels, and a work of creative nonfiction. His latest books are Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, Bookmarked (Ig Publishing) and the novel Lovepain (Braddock Avenue Books).

Pingback: LETTING GO: AN INTERVIEW WITH DILRUBA AHMED (poetry ’09) | Friends of Writers·